Neurodiversity in the workplace: How to build inclusive environments

Talented employees leave after short tenures despite strong technical skills, whilst detail-oriented team members who produce excellent work somehow miss deadlines. Meanwhile, creative staff members struggle in meetings yet consistently deliver outstanding results when working independently.

These patterns often indicate neurodivergent employees working in environments mismatched to how their brains process information. Around 1 in 7 people are neurodivergent [1], meaning they think, learn, and process information differently from conventional expectations. Yet many businesses inadvertently exclude them through unexamined workplace policies.

The numbers tell a stark story: just three in ten autistic people in the UK are in employment [2]. This represents an enormous untapped talent pool.

The business impact extends beyond recruitment costs. Lost productivity from employees working in unsuitable conditions, reduced retention, and missed innovation from unexplored perspectives all affect outcomes. When you consider that employee replacement costs range from 50% to 200% of annual salary, the case for making these adjustments becomes financially compelling.

Summary

- Neurodiversity affects around one in seven people, encompassing conditions such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and dyspraxia [1].

- Barriers arise from systems, not individuals. Standardised hiring, communication, and performance processes often exclude talent unintentionally.

- The business case is clear: small, low-cost adjustments can cut sickness absence and improve retention [14].

- Inclusive recruitment means focusing on essential skills, adapting interviews, and using work samples to assess capability fairly.

- Assistive technology-from built-in text-to-speech to captioning, reminders, and focus tools-helps employees manage information and executive function differences.

- The workplace environment matters: control over noise, lighting, and workspace layout improves comfort and concentration.

- Leadership sets the tone. Inclusive leaders ask “What works best for you?” and reward outcomes, not presentation style.

- The legal foundation: the Equality Act 2010 requires reasonable adjustments, but true inclusion goes further - embedding accessibility into culture and systems.

- Redefining success means valuing contribution over conformity, designing roles around strengths, and treating neurodiversity as a driver of innovation, not a challenge to manage.

What neurodivergent conditions involve

Neurodivergent describes people with autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia, dysgraphia, and Tourette syndrome [1]. Each condition affects how someone's brain processes information.

- ADHD affects attention regulation and executive function. An employee might generate multiple innovative solutions rapidly but require different systems for administrative tasks. The challenge involves working with their cognitive style rather than against it. More than 3 in 100 adults have ADHD [3].

- Autism affects social communication and sensory processing. Around 700,000 adults and children in the UK are autistic [4]. An employee might identify errors others overlook and produce meticulous analysis whilst needing advance notice for schedule changes. Unexpected changes create genuine cognitive disruption rather than mere preference.

- Dyslexia often accompanies strong visual thinking and problem-solving abilities. Around 10% of people in the UK are thought to be dyslexic [5]. Processing written information takes longer, but spatial reasoning and strategic thinking may exceed typical levels. Text-to-speech software addresses the reading challenge - most operating systems include these features without additional cost.

- Dyspraxia affects movement and coordination. At least 1 in 17 people are thought to be dyspraxic [6]. Someone who's dyspraxic might take longer to do some tasks but have strong verbal communication skills and excel at creative thinking.

The changing workforce landscape

Understanding neurodiversity has become increasingly important as workforce demographics shift. Gen Z (people born 1997-2012) now makes up 30% of the workforce, and over half (53%) identify as definitely or somewhat neurodiverse. Perhaps more significantly, 80% of Gen Z prefer to apply to companies that support neurodivergent employees. [1]

This isn't just about attracting younger workers. It's about recognising that 25% of CEOs are dyslexic - though many don't want to talk about it [8]. Neurodivergent traits exist at every level of successful organisations.

Performance and innovation

Research suggests that teams with neurodivergent professionals in some roles can be 30% more productive than those without them [8]. But context matters: JPMorgan Chase's study [9] showed their first cohort of five autistic employees were 48% more productive than colleagues in software quality assurance and performance engineering - with specialised support including dedicated job coaches and week-long work trial periods replacing traditional interviews. The gains came from careful job matching to strengths, not inherent abilities that apply universally.

The data backs this up: companies with mature disability inclusion practices achieve 28% higher revenue and double the net income of competitors [10].

Real-world programmes demonstrate these benefits. DXC Technology's neurodiversity hiring programme shows 92% retention [11] compared to 66% UK average for all employees [12]. Organisations that provide mentors to professionals with disabilities reported a 16% increase in profitability, 18% in productivity, and 12% in customer loyalty [8].

Unique cognitive approaches

Each neurodivergent person is unique, and it wouldn't be accurate to generalise their cognitive process. One neurodivergent leader explained: “When people are discussing something, I can almost see it in my head; I reorganise it and then explain it in simple terms” [8].

Abilities such as visual thinking, attention to detail, pattern recognition, visual memory, and creative thinking can help elevate ideas or opportunities teams might otherwise have missed - individuals with neurodivergent traits bring unique perspectives to the table. By embracing and accommodating these differences, organisations can tap into a diverse pool of talent and drive innovation.

One example of leveraging cognitive diversity is through agile teams. These teams are made up of individuals with different backgrounds, skills, and ways of thinking. This allows for a wider range of ideas and solutions to be explored, leading to more comprehensive and effective outcomes.

Recruitment process improvements

Traditional hiring processes often overlook neurodivergent talent. Yet despite this clear business case, many employees have limited knowledge of neurodiversity, conditions, and symptoms. This lack of awareness often starts at the recruitment stage. Standardised methods - conventional interviews, lack of transparency, insufficient support for different communication styles - often fail to accommodate diverse perspectives [1].

Job description clarity

Many job descriptions include phrases like “excellent communicator” and “strong team player” without defining these terms. This language often codes for neurotypical social behaviour rather than actual role requirements.

List only essential requirements, as each unnecessary preference reduces the talent pool significantly. Before including any qualification or attribute, consider whether someone could still perform the role effectively without it.

Interview format modifications

Traditional interviews assess confidence under pressure and social performance. Unless these represent core job requirements, the process may miss capable candidates whilst advancing others. Providing questions in advance allows candidates to prepare thoughtful responses, shifting the assessment toward reasoning ability rather than quick thinking under pressure.

Work samples offer a more direct demonstration of actual capability: for data analysis roles, provide a dataset to analyse; for writing positions, request writing samples. Observing candidates perform relevant tasks reveals far more than hypothetical scenarios ever could.

Some organisations schedule interviews across several days instead of packing them back-to-back, reducing stress on applicants [1]. Allowing candidates to use their own laptops for tests helps them feel more comfortable [1]. Panel interviews can create sensory challenges - one-to-one conversations or written responses alongside verbal discussions often provide better information about capability.

Expanding role opportunities

Don't categorise neurodivergent people into certain skillsets based on diagnosis. Research shows that when post-secondary institutions examined who was self-identifying as neurodivergent to their accessibility offices, more people self-identified from arts than from STEM, contrary to popular opinion [13].

Organisations should be open to neurodivergent candidates across all departments and roles, not just technical positions. What started as targeted programmes in many companies has evolved into full-time employment models across various functions. Freddie Mac's neurodiversity programme, for example, started with short-term internships and now offers full-time positions across enterprise risk management, IT, and loan processing for people with autism, ADD, ADHD, and dyslexia [14].

Physical environment modifications

Open-plan offices reduce productivity for many employees beyond the neurodivergent population. Research indicates workers in open-plan offices take 62% more sick days [15]. Constant noise, visual distractions, and fluorescent lighting impair concentration.

Practical adjustments include:

- noise-cancelling headphones

- positioning workstations away from high-traffic areas

- creating dedicated quiet spaces separate from social areas

- desk lamps for individual lighting control

- assigned seating to provide consistency.

Remote work eliminates commute stress and reduces sensory input for many neurodivergent employees. However, some individuals require office structure for organisation. Individual preferences vary considerably.

Communication clarity

Workplace communication often relies on ambiguous language, where phrases like "handle this when convenient" or "as soon as possible" create wildly different interpretations—one person understands "this week," another thinks "today," and a third assumes "no urgency." Specific language eliminates this confusion: "Please complete this by Tuesday at 5 PM" provides clear expectations that benefit all employees whilst being essential for those who interpret language literally.

Written confirmation after verbal discussions accommodates different processing styles, recognising that some people absorb information best through conversation whilst others need written material for review and reference. Follow-up documentation takes minutes but prevents hours of confusion.

Compare these approaches:

Unclear: “Can you look into the client issue when you have time and let me know your thoughts?"

Clear: “Please investigate the client's database connection issue. Provide your diagnosis and proposed solution by Thursday at 2 PM for response before their Friday deadline."

Some neurodivergent individuals benefit from specific, step-by-step instructions rather than broad directives. Breaking down tasks into concrete actions with clear verbs helps: instead of “prepare the room,” try “vacuum the floor, dust the surfaces, and arrange six chairs in a circle."

Meeting agendas distributed in advance improve participation. List discussion topics, required decisions, and necessary preparation. This enables all attendees to contribute effectively rather than processing information and formulating responses simultaneously.

Multiple communication channels accommodate different preferences:

- Email for written information processing

- Messaging platforms for brief questions

- Regular one-to-ones for complex discussions

- Visual tools like flowcharts for process documentation

Not everyone communicates most effectively through identical methods.

Individual management approaches

Specific feedback delivery

Many managers provide indirect feedback or use "sandwich" approaches where criticism appears between compliments, but this often creates confusion rather than clarity. Direct, specific feedback serves everyone better: "The analysis was thorough and identified three calculation errors. The report needs shorter paragraphs and more headings for easier scanning" indicates exactly what to maintain and what to adjust, whereas "Good work overall, but readability could improve" lacks actionable detail.

Written feedback creates valuable reference material, particularly since verbal discussions fade from memory or become misremembered. Documentation helps employees track progress and clarify expectations over time.

Flexibility in working patterns

Some employees produce exceptional work in intensive blocks but struggle with steady eight-hour routines, whilst others work most effectively during off-peak hours with fewer interruptions. Where roles permit flexibility, allowing it improves outcomes - so focus on results rather than uniform processes. Consider whether specific methods genuinely affect work quality: does note-taking method during meetings matter if the work gets completed effectively? Do email response times matter if communication remains adequate?

Breaking large projects into milestones with defined deadlines creates helpful structure. "Launch the new website by June" can overwhelm employees with executive function challenges, whereas "Complete homepage design by 15 March, build pages by 30 April, test and launch by 15 June" provides clear progression. Similarly, matching tasks to strengths improves efficiency: employees who excel at pattern recognition suit quality control work, those who generate creative solutions handle innovation projects, and those with strong spatial thinking lead design initiatives.

This approach benefits team performance broadly, as research indicates that diverse cognitive styles improve problem-solving. Teams with varied thinking patterns challenge assumptions and identify solutions that homogeneous groups overlook.

Providing mentorship and support

Mentors provide much-needed support to all workers' careers, but they're perhaps even more important for the development of the neurodivergent workforce [8]. A mentor can be an advocate for the professional, playing an active role in creating opportunities and, over time, empowering the individual to build relationships and create other professional allies across the organisation [8].

In addition to mentors, work buddies and trusted peers who make the effort to understand the individual and provide long-term commitment can help neurodivergent professionals feel more empowered. .

Assistive technology and tools

Assistive technology (AT) refers to software, hardware, or built-in system features that help employees perform tasks in a way that better matches how they process information. For neurodivergent people, AT can reduce unnecessary effort and enable them to work at their best without constant workaround strategies.

AbilityNet notes that many adjustments rely on existing technology and cost very little to implement [16]. Most operating systems already include accessibility functions that can be activated by employees or configured centrally through IT support.

The key is not to prescribe one solution for all, but to match tools to individual needs and make sure everyone knows what options exist.

Reading, writing, and comprehension support

Some employees find written communication or dense documents difficult to process. Built-in accessibility features can remove barriers without altering the work standard.

- Text-to-speech converts written material into spoken words, useful for dyslexic or visually sensitive employees. Available on all major platforms, including Windows, macOS, Android, and iOS.

- Speech-to-text (dictation) supports those who process thoughts verbally or find typing fatiguing. Both Microsoft 365 and Google Workspace include secure dictation features.

- Adjustable display settings - such as font type, size, colour contrast, and spacing - help reduce eye strain and improve comprehension.

- Focus or reading modes simplify layouts by removing visual clutter from webpages or documents. Microsoft’s Immersive Reader and Google Chrome’s Reader Mode are examples.

Encourage employees to explore the accessibility section of their operating system or software suite. Managers can signpost internal IT guides or short training sessions during onboarding. The goal is to normalise accessibility rather than reserve it for those who disclose a condition.

Planning, organisation, and time management

Executive function differences can make prioritising or sequencing tasks difficult. Digital planning tools can externalise structure and support reliable time management.

- Calendar and reminder systems (e.g. Outlook or Google Calendar) provide visual timelines, recurring task lists, and pop-up reminders.

- Digital to-do lists or task boards allow projects to be broken into clear steps. Many collaboration suites include these as standard.

- Visual timers and focus modes support concentration by showing time passing and blocking distractions. Windows and macOS both now include “Focus Assist” or “Do Not Disturb” options.

- Automated email rules or filters reduce cognitive overload by grouping messages and setting clear notification priorities.

Teams can agree on shared planning tools so that everyone benefits from clarity and consistency. Managers should avoid imposing a single method but make options visible and offer flexibility in how staff manage their time.

Communication and meeting accessibility

Workplaces often reward quick verbal processing, which can disadvantage neurodivergent employees. Accessible communication tools make collaboration more equitable.

- Live captions and meeting transcription are built into Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, and Zoom. These allow participants to follow discussions more accurately and review them later.

- Meeting recording and summarisation features support employees who need extra time to process or review complex information.

- Visual collaboration spaces such as shared whiteboards or diagramming tools help people communicate ideas visually rather than verbally.

- Follow-up summaries - created with standard office tools - ensure that decisions and actions are clear, reducing miscommunication for everyone.

Use captions and summaries by default, not on request. Send agendas in advance and note key decisions afterward. These practices require minimal effort but make meetings significantly more accessible.

Sensory and environmental adjustments

For autistic, ADHD, and dyspraxic employees, environmental control can affect performance as much as digital tools. Adjustments should be straightforward and employee-driven.

- Noise control. Offer quiet spaces, sound-dampening areas, or the option to use noise-reducing equipment.

- Lighting. Provide adjustable desk lighting or alternatives to fluorescent bulbs where possible.

- Screen comfort. Offer guidance on using system settings such as “dark mode,” “night light,” or blue-light filters to reduce visual stress.

- Hybrid and remote work options. Flexibility in work location can reduce sensory overload and improve concentration for some employees.

Include sensory preferences in workplace setup checklists (for example, preferred desk location or lighting). Facilities and HR teams can work together to document and maintain these adjustments.

Coaching and integration

Technology only works when employees know how to use it confidently. Short, structured training or coaching ensures tools become embedded in everyday practice.

- Assistive technology training can be funded through the UK’s Access to Work [17] scheme. This may include workplace assessments and one-to-one coaching on how to use accessibility software effectively.

- Peer support or employee networks can help share knowledge and normalise accessibility tool use across the organisation.

- Inclusive IT induction: introducing accessibility settings during general onboarding ensures everyone knows what’s available before a need arises.

Keep information about accessibility tools visible on intranet pages, and ensure IT helpdesks are briefed to support their setup. The goal is for every employee, not only those who disclose, to know these tools exist.

Embedding technology into everyday systems

Assistive technology works best when it’s treated as standard, not exceptional. The CIPD recommends that organisations integrate accessibility and neuroinclusive design into all digital systems and processes [18].

Examples include:

- enabling captions and transcripts by default in meetings

- ensuring training materials are compatible with screen readers

- adopting clear, consistent document templates

- promoting flexible sensory and communication options in workstation setup.

Embedding these practices moves inclusion from individual accommodation to organisational culture - benefiting everyone, not just those who identify as neurodivergent.

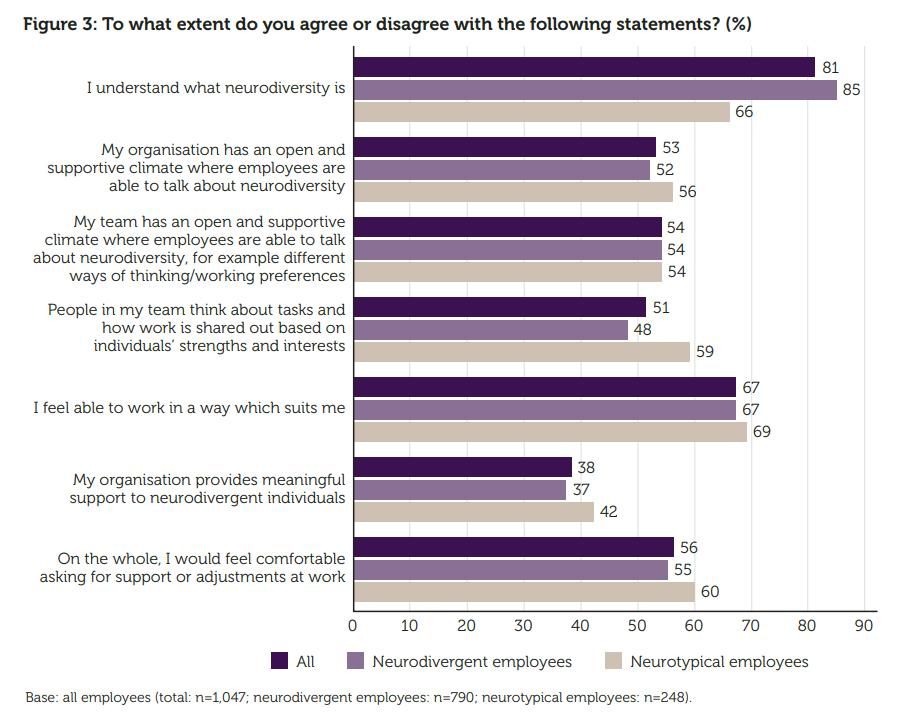

Yet even with growing awareness, a gap remains between understanding and consistent action. The CIPD Neuroinclusion at Work Report (2024) [18] shows that while a large majority of employees (81%) say they understand what neurodiversity is, only 38% feel their organisation provides meaningful support, and just over half feel comfortable asking for adjustments.

As illustrated below, this mismatch between awareness and lived experience highlights a persistent cultural barrier: employees often recognise the importance of neurodiversity but don’t see it reflected in everyday systems.

For assistive technology to have real impact, it must be supported by a culture where using accessibility tools and requesting adjustments is normalised rather than stigmatised. When inclusion becomes the default, engagement and confidence rise across the workforce.

Employee perspectives on neurodiversity awareness and support. Source: CIPD, 2024. [18]

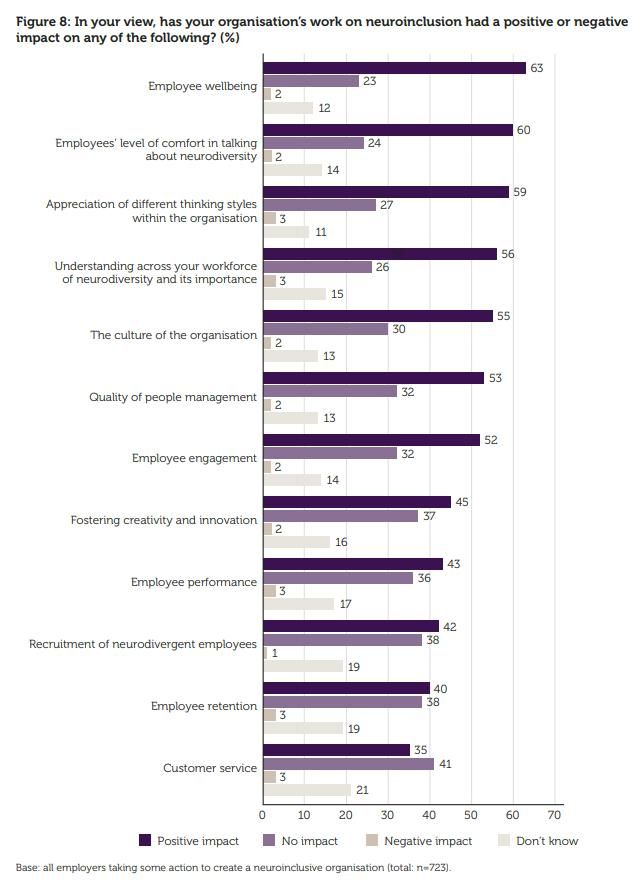

The organisational impact of embedding such inclusive systems is equally significant. According to the same report, employers that have acted on neuroinclusion report measurable improvements across multiple areas - 63% see higher employee wellbeing, 60% report greater comfort discussing neurodiversity, and over half note stronger organisational culture and management quality.

As shown in the below chart, these outcomes demonstrate that neuroinclusion is not just about fairness; it directly enhances performance, engagement, and retention. When accessibility and flexibility are built into everyday systems - supported by leadership, training, and accountability - technology shifts from a reactive adjustment to a driver of sustainable, inclusive growth.

Organisational impact of neuroinclusion activity. Source: CIPD, 2024. [18]

Implementing neuroinclusion: A practical framework

Becoming a neuroinclusive organisation doesn’t require an overhaul - it requires deliberate sequencing. The most effective approaches start small, measure impact, and expand systematically. A structured process helps inclusion move from isolated initiatives to sustainable practice.

1. Audit existing systems

Review recruitment, communication, and performance processes for hidden barriers. Check whether job adverts overstate social expectations, whether meetings rely on fast verbal processing, and whether technology settings are fully accessible. Tools such as the CIPD’s Diversity Calendar or the Business Disability Forum’s self-assessment tools provide useful starting points.

2. Adjust and pilot

Introduce low-cost, high-impact changes first - clearer written communication, meeting agendas circulated in advance, captioning in virtual meetings, and workspace lighting options. Trial these with volunteer teams, gather feedback, and refine. The goal is to integrate inclusion into normal workflows rather than treat it as an add-on.

3. Embed and educate

Once adjustments prove effective, formalise them in policy and training. Include accessibility options in IT induction, train managers on inclusive communication, and ensure HR processes reference neurodiversity explicitly. Embedding neuroinclusion into leadership and performance frameworks makes it self-sustaining rather than dependent on individual champions.

Cost of adjustments and how to fund them

Access to Work: The UK government funding

Access to Work grants reach up to £69,260 annually as of April 2024-March 2025 [19]. This publicly funded employment support provides practical and financial help for people with disabilities to start or stay in work. The grant doesn't need repayment and won't affect other benefits.

It covers:

- specialist equipment and software

- support workers including job coaches and note-takers

- travel costs and vehicle adaptations

- physical workplace changes

- workplace assessments

- disability awareness training for colleagues

- mental health support.

Cost and funding options

| Item | Cost Range | Typically Funded By |

|---|---|---|

| Workplace needs assessment | £195 - £350 | Free through Access to Work |

| Noise-cancelling headphones | £28-£40 (basic) to £200-£500 (professional) | Access to Work for eligible employees |

| Assistive software | Typically licensed via workplace or Access to Work, not retail | Access to Work |

| Coaching (neurodiversity or assistive tech) | £50-£100+ per hour | Access to Work or employer |

| Autism awareness training | £30 - £175 | Access to Work or employer |

For more information, visit:

Creating a culture of belonging

Exclusion is simply not an option. However, merely acknowledging and accepting individual differences, without taking further action, is also not enough. While well-intentioned, concepts like "tolerance" and "acceptance" can sometimes imply a conditional welcome, where norms might still be set by a dominant group. These approaches can also inadvertently place a person's "difference" before their individuality. For genuine cultural transformation, organisations need to evolve beyond exclusion and actively foster a sense of belonging. [8]

Organisations can foster this feeling of belonging, broadly, in three ways, as per Deloitte [8]:

- Comfort. Neurodivergent professionals have the freedom to bring their authentic self to work and are treated fairly.

- Connection. Professionals identify themselves with a defined team (function, department, geography, etc.) and have a sense of community with their peers.

- Contribution. Professionals are valued for their individual contributions, and they feel aligned with the organisation's purpose, mission, and values.

Addressing masking

Neurodivergent employees might mask their condition at work. Masking means hiding parts of a condition to fit in better. Someone might not be aware they're doing it. Being neurodivergent means facing challenges that a neurotypical person doesn't have to, especially as people with neurodivergent differences are more at risk of having mental illnesses or poor wellbeing. This is often due to a lack of support, and the stress of 'masking' - acting neurotypically in order to avoid stigma or a negative response.

Masking can cause mental health problems. It can make someone feel exhausted, isolated, and like they cannot be themselves.

People might not need to mask as much if they feel comfortable at work. Employers can help by taking steps to make their organisation neuroinclusive and thinking carefully about how they talk about neurodiversity.

The Equality Act 2010: What you're required to do

The legal definition

A person has a disability if they have a physical or mental impairment, and the impairment has a substantial and long-term adverse effect on their ability to carry out normal day-day activities [7].

(See: Equality Act 2010)

What ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ mean:

- substantial means more than just a minor impact on someone’s life or how they can do certain things - taking much longer to complete daily tasks

- long-term means lasting or likely to last at least 12 months.

Crucially: no formal diagnosis is required [21]. Tribunals assess impact on daily activities. Neurodivergent conditions may meet this threshold. Fluctuating conditions may qualify if the effects are substantial when active.

Reasonable adjustments

Once an employer knows or ought to know that someone has a disability, reasonable adjustments become mandatory [22]. The questions below can help you determine reasonableness.

- Will it remove or reduce the disadvantage?

- Is it practical?

- Is it affordable?

- What's the health and safety impact?

Small employers are judged differently than large corporations on affordability [23]. Most effective adjustments cost nothing: flexible hours, written instructions, regular check-ins, designated quiet workspace.

The financial risk

In the 2023/2024 financial year, the average disability discrimination award was £44,483 [24], but penalties can be much higher, with a maximum recorded penalty of £4.6 million in a 2024 ADHD/PTSD case [25].

Recent tribunal cases highlight the significant financial risks for employers. In Borg-Neal v Lloyds Banking Group (2023) [26], a dyslexic employee who was summarily dismissed for using an inappropriate term during race awareness training won £470,000. The tribunal found that their disability affected how he phrased a legitimate question, and dismissing them amounted to discrimination. Furthermore, tribunals can increase awards by up to 25% [27] if employers unreasonably fail to follow the ACAS Code of Practice on disciplinary and grievance procedures.

Measuring progress and accountability

Neuroinclusion becomes meaningful when organisations can see - and demonstrate - change. Tracking outcomes helps identify what works, supports transparency, and strengthens the business case for continued investment.

Key indicators you can start monitoring:

- Recruitment and retention: number of neurodivergent hires, retention rates, and promotion outcomes compared with baseline data.

- Employee experience: inclusion or engagement survey results, specifically whether staff feel comfortable disclosing neurodivergence or requesting adjustments.

- Adjustment uptake: number of employees using accessibility features, assistive technology, or flexible working options.

- Training: completion of neuroinclusion or accessibility training by people managers.

- Process evaluation: accessibility audits of digital systems, communication templates, and meeting formats.

Data should be anonymised and voluntary but reported consistently. As ACAS guidance notes [28], evidence-based monitoring allows organisations to move beyond intention to measurable impact - and to identify where support still falls short.

Redefining success: What neuroinclusion really means

Neuroinclusion is not about lowering expectations or creating exceptions; it’s about defining success by contribution rather than conformity. Traditional measures often reward visibility and verbal fluency over substance, unintentionally overlooking those whose strengths lie in accuracy, innovation, or creative insight.

True inclusion asks a more practical question: what conditions allow each person to perform at their best, and are we designing work to enable that? When managers focus on outcomes, communication flexibility, and sustainable workloads, they build environments where different minds can succeed without masking or burnout.

Leaders play a central role in shaping this culture. Asking “What works best for you?” and treating adjustments as routine rather than special sends a powerful message: inclusion is not an initiative - it’s how effective organisations operate. When systems evolve to fit people, rather than the reverse, retention, trust, and innovation follow naturally.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. The information is accurate at the time of writing but may be subject to change. For advice specific to your situation, please consult a qualified professional.

[1] Microsoft, Neurodiversity Program: case study, 2025.

[2] Department for Work and Pensions, The Buckland Review of Autism Employment: report and recommendations, February 2024.

[3] ADHD UK, What is ADHD - About ADHD.

[4] National Autistic Society, What is autism.

[5] NHS, Dyslexia, March 2022.

[6] Foundation for People with Learning Disabilities, Dyspraxia.

[7] GOV.UK, Equality Act 2010: guidance, October 2025.

[8] Deloitte, Neurodiversity in the workplace - Deloitte Insights, January 2022.

[9] JPMorgan Chase, Autism at Work program opens doors for those on the spectrum - Employee Benefit News, September 2020.

[10] Accenture, Companies Leading in Disability Inclusion Have Outperformed Peers, Accenture Research Finds, October 2018.

[11] DXC Technology, DXC Dandelion Program Overview, 2021.

[12] CIPD, Benchmarking Employee Turnover - CIPD Voice.

[13] Parliamentary Committees, More arts neurodivergent self-identification than STEM.

[14] Next for Autism, Freddie Mac neurodiversity programme.

[15] U.S. National Library of Medicine, Open-plan office study, July 2023.

[16] AbilityNet, What are reasonable adjustments - workplace accessibility guide.

[17] GOV.UK, Access to Work factsheet for customers.

[18] CIPD, Neuroinclusion at Work Report, 2024.

[19] GOV.UK, Access to Work grant expenditure forecasts.

[20] GOV.UK, Definition of disability under Equality Act 2010.

[21] ACAS, What disability means by law.

[22] ACAS, Reasonable adjustments: disability at work.

[23] Middleton Law Ltd, Neurodiversity and reasonable workplace adjustments.

[24] BBC, Hammersmith and Fulham Council boss speaks out over £4.6m pay-out, March 2024.

[25] GOV.UK, Tribunals statistics quarterly: April to June 2024, October 2024.

[26] Hill Dickinson LLP, Discrimination: £470K compensation awarded dyslexic employee - Borg-Neal v Lloyds Banking Group (2023), 2024.

[27] MFMAC, 25% ACAS code uplifts endorsed - employment tribunal guidance, 2024.

[28] ACAS, Neurodiversity at work: making your organisation neuroinclusive.